Article 33 of the UN Charter:

(2) State-State Arbitration

Presentation:

International Boundary Disputes and Natural Resources

Throughout history, empires and kingdoms expanded through invasion, occupation, conquest and colonisation or discovery. Expansion of empires often proceeded in concert with exploitation of natural resources. Colonization often resulted in massive exploitation of natural resources in Africa, Asia, America. Local economies were restructured to ensure a flow of human and natural resources between the colony and the colonizing state. 18. and 19. centuries heralded exponential growth in demand for energy generating natural resources and the commencement of large-scale coal mining.

Two aspects of geography frequently give rise to international boundary disputes:

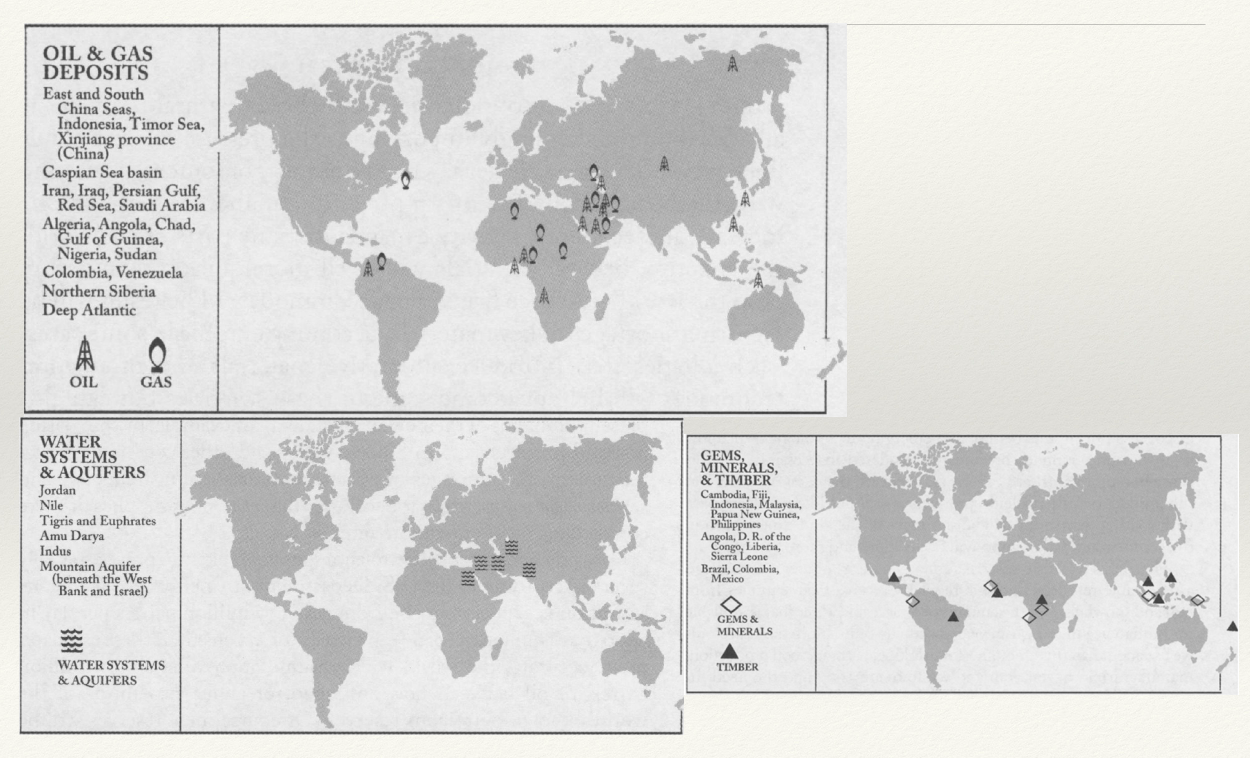

The New Geography of Conflict

Global energy demand continues to grow. Global population is increasing. The vast majority of the world’s rapidly increasing energy needs are met through fossil fuels.

Increased competition over access to major sources of oil and gas, growing friction over the allocation of shared water supplies, and internal warfare over valuable export commodities have produced a new geography of conflict.

Contested oil and gas fields, shared water systems, embattled diamond mines – provide a guide to likely conflict zones in 21st century.

Boundary Disputes

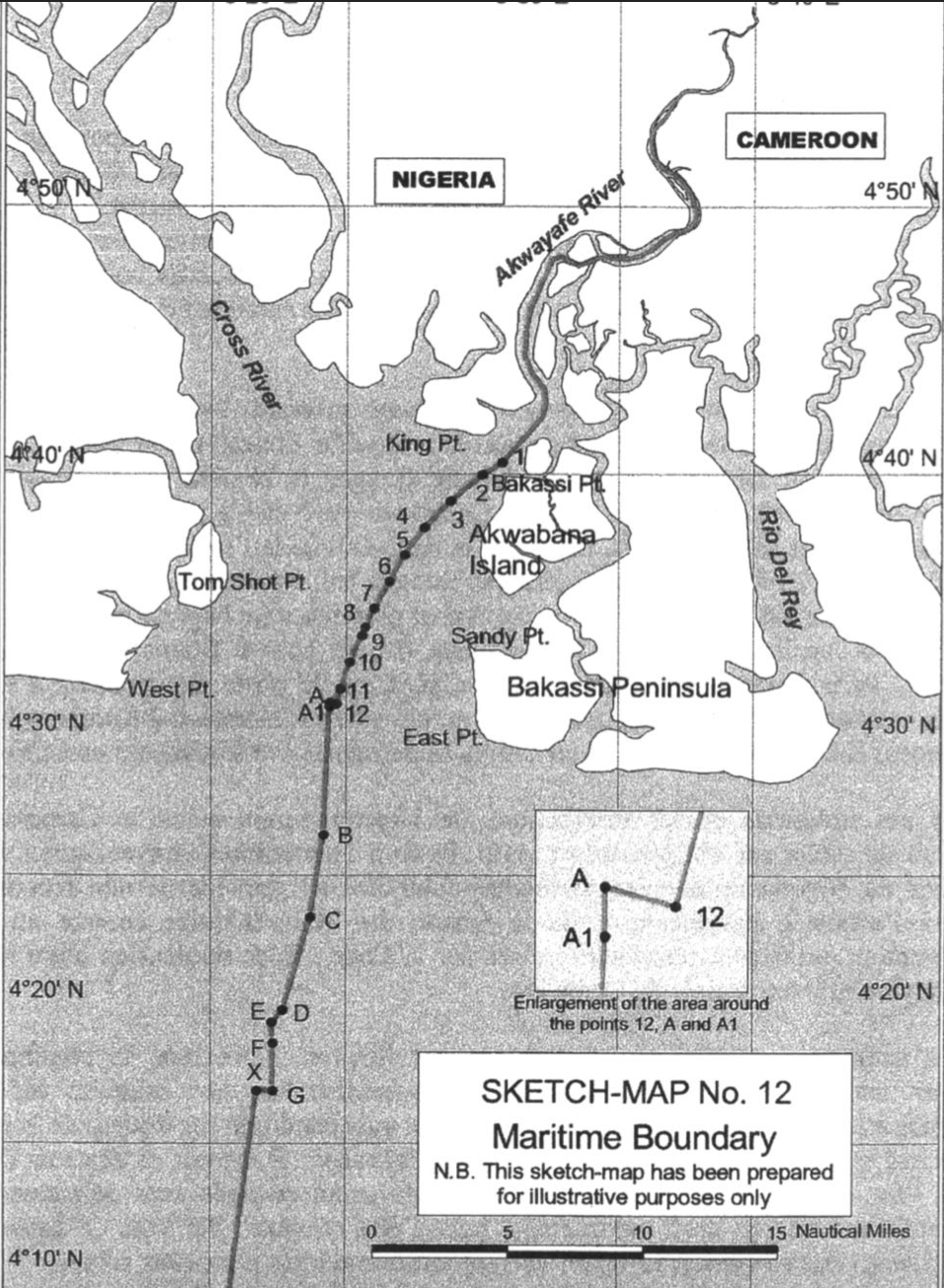

Oil-rich Bakassi Peninsula (Cameroon v. Nigeria)

Historical context:

Cameroon declared independence in 1960 (French). Nigeria declared independence in 1960 (UK). The status of British Cameroons was unclear. A United Nations-sponsored plebiscite took place: The northern part of the territory voting to remain part of Nigeria, while the southern part voted for reunification with Cameroon. The northern part of British Cameroons was transferred to Nigeria, while the southern part joined Cameroon.

However, the land and maritime boundaries between Nigeria and Cameroon were not clearly demarcated. One of the disputes areas was - the Bakassi Peninsula, an area with large oil and gas reserves. The two countries nearly going to war on 16 May 1981, when five Nigerian soldiers were killed during border clashes. As the clashes continued until 2002, Cameroon referred the matter to the ICJ requesting that it determine the question of sovereignty over the oil-rich Bakassi Peninsula and a parcel of land in the area of Lake Chad. Cameroon also asked the Court to specify the land and maritime boundary between the two states, and to order an immediate and unconditional withdrawal of Nigerian troops from alleged Cameroonian territory in the disputed area.

On October 10, 2002, the Court ruled that sovereignty over the Bakassi Peninsula and the Lake Chad area lay with Cameroon.

Dispute settlement:

State - State Arbitration

INTER-STATE arbitration is largely influenced by two different traditions,

Example: in 1493, Pope Alexander IV decided the geographical dispute between Spain and Portugal over the division of their colonial empires; the Jay Treaty of 1796 between the USA and Britain provided for arbitration as a quasi-judicial means in response to the American Revolution (Its commissions produced more than 500 decisions over five years.)

B) Commercial tradition: Transnational arbitration between merchants, before an impartial tribunal of the parties’ choosing, under an established procedure, pre- dates the emergence of nation-states.

Arbitration traditionally addressed only existing disputes. However, by the end of the nineteenth century it was becoming necessary to introduce an arbitration mechanism for future disputes between states, as existed for commercial arbitrations between merchants. Such an obligatory arbitration, agreed by states in advance of a dispute, was addressed at length by the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907.

It called for an international conference between states to ensure a true and stable peace and, above all, to put an end to the progressive development of modern armaments. It was thus to be primarily a peace conference at a time when several European states maintained standing forces measured in millions of soldiers and sailors, absorbing 25 per cent or more of state revenues.

For such states, including Russia, these ruinous and ever-increasing costs threatened national security almost as much as armed conflict. The 1899 Conference was also to take place within living memory of Germany’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War 1870–71, with France’s lost territories in Alsace and Lorraine still unrecovered, the conflict between Chile and Peru in 1882, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, the war between Greece and Turkey in 1897, the Spanish– American War of 1898 and, as regards incipient armed conflict, the ‘Fashoda incident’ between France and Britain also in 1898.

The eventual result was a consensus in the form of The Hague Convention on the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes, which entered into force on 19 September 1900 (the 1899 Hague Convention). It created the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), which was neither a court nor an arbitration tribunal, still less a permanent court or arbitration tribunal. It was nonetheless a permanent mechanism comprising a secretariat, a registry, and a chamber of senior jurists appointed by the contracting states as potential arbitrators. The issue of obligatory arbitration was, however, rejected.

The Conference led to the replacement of the 1899 Convention with the 1907 Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (the 1907 Hague Convention). The issue of obligatory arbitration was again raised by the delegations from the USA and Portugal supported by Martens (Russia) and Léon Bourgeois (France). It was again strongly opposed by Germany. There was to be no permanent international court and no obligatory arbitration.

Between 1899 and 1914, under the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, there were eight references to arbitration before the PCA, together with two commissions of inquiry.

There was also a change in the practice of several states agreeing bilateral treaties providing for obligatory arbitration in conformity with the Russian proposal at the first Hague Conference. For example, Art. 1 of the 1911 Franco-Danish treaty provided that future differences of a juridical character shall be submitted to arbitration provided that ‘they do not affect the vital interests, independence or honour of either of the contracting parties nor the interests of third Powers’ (obligatory arbitration);

There were, however, indirect results from the Hague Conferences: the creation of the Permanent Court of International Justice (1925) and, after the Second World War, the International Court of Justice (1946), with their jurisdictions capable of agreement prior to a dispute under Art. 36 and 36(2) respectively.

As to the eventual agreement of many states to different forms of obligatory arbitration, between 1899 and 1999, 33 disputes were referred to the PCA and, from 1999 to 2016, a further 180 disputes. These included many obligatory arbitrations. Even where there exists a permanent international court as an alternative forum, several states have preferred inter-state arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS administered by the PCA, to inter-state litigation before ITLOS in Hamburg. The PCA’s membership has increased from 71 contracting states in 1970 to 122 contracting states in 2020.

Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

International Boundary Disputes and Natural Resources

The Government of Sudan / The Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (Abyei Arbitration)

Historical context:

Sudan is a former British colony.

North Sudan – Arab peoples

South Sudan – ethnically African Christians and tribes with traditional religious beliefs in the south.

Since 1956, when the British left Sudan, ethnic differences led to many years of civil war. In 1970s the south was given regional autonomy. However, after the discovery of oil reserves there, civil war erupted again. In 2005, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed – nonetheless, the demarcation of Abyie – an oil-rich area was disputed. On July 11, 2008, the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement deposited an Arbitration Agreement with the PCA. Dispute over the boundaries of the oil-rich Abyei area. (Oil makes up 98% of South Sudan’s revenues)

Abyei is situated within the Muglad Basin, a large rift basin which contains a number of hydrocarbon accumulations. Oil exploration was undertaken in Sudan in the 1970s and 1980s. A period of significant investment in Sudan’s oil industry occurred in the 1990s and Abyei became a target for this investment. By 2003 Abyei contributed more than one quarter of Sudan’s total crude oil output. Production volumes have since declined and reports suggest that Abyei’s reserves are nearing depletion. An important oil pipeline, the Greater Nile Oil Pipeline, travels through the Abyei area from the Heglig and Unity oil fields to Port Sudan on the Red Sea via Khartoum. The pipeline is vital to Sudan’s oil exports which have boomed since the pipeline commenced operation in 1999.

The dispute focused on whether a commission of experts, the ‘Abyei Boundaries Commission’ (ABC Experts), exceeded their mandate in determining the region’s borders. The area is important for the 2011 referendum on independence of South Sudan under the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement.

On 22 July 2009 the tribunal delivered its Final Award. It found that the ABC Experts had not exceeded their mandate in adopting a “tribal” interpretation but had exceeded the mandate by failing to give sufficient reasons for their conclusions regarding the Northern shared boundary and the Eastern and Western boundaries. Based on scholarly, documentary and cartographic evidence, the tribunal delimited the regions new borders. It reduced the size of the region and gave greater territorial control to the Government of Sudan to the areas containing oil fields.

Raw Materials related disputes (!!! WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism is not considered to be an arbitration)

DS394: China — Measures Related to the Exportation of Various Raw Materials

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds394_e.htm

DS431: China — Measures Related to the Exportation of Rare Earths, Tungsten and Molybdenum

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds431_e.htm

Both cases concern certain measures imposed by China affecting the exportation of certain forms of raw materials.

Hydropower related disputes

The Indus Waters Treaty 1960

The Indus Waters Treaty is an international agreement signed by India and Pakistan in 1960 that regulates the use by the two States of the waters of the Indus system of rivers. Seen as one of the most successful international treaties, it has survived frequent tensions, including conflict, and has provided a framework for irrigation and hydropower development for more than half a century.

Eastern and Western Rivers:

a) All the waters of the Eastern Rivers shall be available for the unrestricted use of India.

b) Pakistan shall receive for unrestricted use all waters of the Western Rivers which India is under obligation to let flow under the provisions of Paragraph (2). However, India shall be under an obligation to let flow all the waters of the Western Rivers, and shall not permit any interference with these waters, except for the following uses specified by the Treats, such as a generation of hydro-electric power (as set out in Annexure D)

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms:

The Treaty sets out a mechanism for cooperation and information exchange between the two countries regarding their use of the rivers, known as the Permanent Indus Commission, which has a commissioner from each country. The Treaty also sets forth distinct procedures to handle issues which may arise: “questions” are handled by the Commission; “differences” are to be resolved by a Neutral Expert; and “disputes” are to be referred to a seven-member arbitral tribunal called the “Court of Arbitration.”

See: Indus Rivers Treaty

(1) INDUS WATERS KISHENGANGA ARBITRATION (2013)

Decided by the Court of Arbitration as specified in the Indus Waters Treaty, The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) acted as Secretariat to the Court of Arbitration.

A dispute between Pakistan and India under the Indus Waters Treaty involving the Kishenganga Hydro-Electric Project (the “KHEP”) located on the Kishenganga/Neelum River. Pakistan challenged, in particular, the permissibility of the planned diversion by the KHEP of the waters of the Kishenganga/Neelum into the Bonar Nallah and the effect that this diversion would have on Pakistan’s Neelum-Jhelum Hydro-Electric Project (the “NJHEP”), also currently under construction on the Kishenganga/Neelum downstream of the KHEP.

On February 18, 2013, the Court had issued a Partial Award, in which it unanimously decided that the KHEP is a Run-of-River Plant within the meaning of the Indus Waters Treaty and that India may accordingly divert water from the Kishenganga/NeelumRiver for power generation. However, the Court also decided that India is under an obligation to construct and operate the KHEP in such a way as to maintain a minimum flow of water in the Kishenganga/Neelum River, at a rate to be determined subsequently.

In its Final Award dated December 20, 2013, which is binding upon the Parties and without appeal, the Court of Arbitration unanimously decided the question of the minimum flow that was left unresolved by the Partial Award. The Court decided that India shall release a minimum flow of 9 cbm per second into the Kishenganga/Neelum River below the KHEP at all times.

(2) DISAGREEMENT ABOUT THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE KISHENGANGA AND RATLE HYDROELECTRIC POWER PLANTS (SINCE 2016)

India and Pakistan disagree about the construction of the Kishenganga (330 megawatts) and Ratle (850 megawatts) hydroelectric power plants being built by India. The two countries disagree over whether the technical design features of the two hydroelectric plants contravene the Indus Waters Treaty.

The Indus Water Treaty provides for following dispute settlement mechanism (Article IX of the Indus Waters Treaty):

Pakistan asked the World Bank to facilitate the setting up of a Court of Arbitration to look into its concerns about the designs of the two hydroelectric power projects. India asked for the appointment of a Neutral Expert for the same purpose.

On December 12, 2016, World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim announced that the World Bank would pause before taking further steps in each of the two processes requested by the parties. Both India and Pakistan stated that processing the requests regarding the Neutral Expert and Court of Arbitration simultaneously presented a substantial threat to the Treaty, since it risked contradictory outcomes and worked against the spirit of goodwill and friendship that underpins the Treaty. The announcement by the Bank to pause the processes was taken to protect the Treaty in the interests of both countries.

Since late 2016, the World Bank has sought an amicable resolution to the most recent disagreement and to protect the Treaty.

See

Maritime Boundary Arbitration

to be discussed on 12 April 2021

(https://pca-cpa.org/en/services/arbitration-services/unclos/)