Various manifestations can be brought about by harmful factors. When establishing the diagnosis of a disease of the oral mucosa, one has to take into account the general variability of pathological processes, the individual response of a particular individual and – last but not least – the specific features of the oral environment, which characterize a particular disease but can also lead to diagnostic uncertainty (morphea maceration in wet conditions, dificulty in finding the blister roof due to mastication, etc.). In order to establish the exact diagnosis, it is necessary to take into account the distribution of lesions and their clinical appearance as well as the patient history and the results of additional tests (histology, serology …).

Patient examination includes:

Patient history

Objective finding

Additional tests

Specialist examinations and consultations

Family history | Family predisposition to the disease |

Personal history | Is the patient in the care of other doctors - why? Hospitalization, surgery, complications Pregnancy Health problems (heart, blood pressure, bleeding, DM, thyroid gland, stomach and intestines, kidneys, liver, infectious hepatitis; metabolic, immune, hormonal disorders) Skin disease Allergy Medication (intolerance, side effects) Smoking and other bad habits |

Current disease | Why is the patient coming and who sent the patient? Type of trouble? Time data:

Course and development of symptoms

Relation of the first symptoms to

Intensity of symptoms

Previous treatment and its effect |

Taking the patient history is an indispensable part of any examination. The procedure is identical with that used in other medical fields – it includes the family and personal history and detailed questioning regarding current diseases. As for the present diseases, the following pieces of information are collected: when the disease manifested and how long it has been present, how it is associated with external and internal factors, what is the intensity of the local and general symptoms. The talk usually starts with the following questions: when did the disease first appear, how long has it lasted, and did it occur for the first time or repeatedly.

Recurrences are typical of recurrent aphthae whereas seasonality is characteristic e.g. for erythema exsudativum multiformae Hebrae (EEM) one however has to take into account that the presenting patient may only have his/her first attack of the disease. Subsequently, possible links are investigated – the patient often recalls some facts only after a targeted question (e.g. consequences of a dental treatment such as stomatitis caused by cotton wool swabs used for drying out the mucosa, allergic reaction after the use of a new product – cosmetic products, toothpaste, etc.). Information on the speed of the development of symptoms is also important – the treatment of acute symptoms must be initiated quickly whereas in case of chronic problems, it is usually possible to wait for results of additional tests.

The subjective information about pain – be it spontaneous pain or pain induced by a stimulus – is also very important since it is usually typical of acute conditions. Contrary, painlessness is a typical feature of some diseases (syphilis, carcinoma), although an inflammatory modification is possible (for example secondary infection).

Bleeding is another symptom occurring when the integrity of the mucous surface is affected, especially obvious where vessels have been afflicted. It may also be a sign of serious changes in the blood count (leukemia, agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia or thrombocytopathy) or occur as a result of some medications (anticoagulants, antiaggregants, etc.).

Mouth odour (foetor ex ore) is another frequently examined symptom accompanying the diseases of the oral mucosa. It can be a non-specific symptom of poor hygiene (which may represent the etiological cause or just patient’s efforts to avoid pain). A typical sweetish odour is usually associated with necrotic mucosal decomposition (e.g. in ulcerative gingivostomatitis or leukaemia-associated necrosis).

The disorders of salivation – hyposalivation or hypersalivation – may also accompany oral mucosal diseases. Xerostomia is usually associated with fever, being typical of the Sjögren, Mikulicz or Felty syndromes. They may occur at dehydration of different origins, atherosclerosis, after the use of some medication or radiation therapy. Hypersalivation usually occurs at acute inflammations of the oral mucosa (herpetic gingivostomatitis, epidemic stomatitis) or heavy metal poisoning.

General symptoms preceding the symptoms in the oral cavity may also represent a part of the clinical picture of the disease (for example prodromes during herpetic gingivostomatitis). At other times, they may represent an individual disease reducing the systemic immunity and thus indirectly affecting the findings on the oral mucosa (herpes simplex after getting chilled). If parallel to local symptoms, the general symptoms can indicate a potentially serious general disease (necroses associated with acute leukaemia) or a metabolic disorder (candidiasis in diabetic patients).

Easy access is the main advantage. Visual inspection should always include palpation in order to identify any unevenness of the surface, the consistency and size of formations, the mobility and relationship to the surrounding tissues, and pain. The examination should proceed at perfect lighting. Attention is paid to the face as a whole, the oral cavity, tonsils, nasopharynx, as well as the submandibular and cervical regions. The examination of the oral cavity starts systematically with the lips and mouth corners, followed by the vestibular region, dental arches including the marginal periodontium, the dorsum and base of the tongue, the base of the oral cavity, buccal mucosa, hard and soft palates and palatine arches with the uvula and the outlets of large salivary glands. Any changes in the mucosa are examined, paying attention to the colour, thickness, and moisture of the mucosa, the presence of mucosa-associated efflorescences, and the localization and extent of any affliction.

The colour of the mucosa shows both racial and individual variations. Normally, the mucosa has a light pink colour; in patients with anaemia, the mucosa is paler, white colour is typical of hyperkeratosis and leukoedema whereas red (erythematous) mucosa is characteristic of inflammations. Sometimes, physiological or pathological pigmentations can be found.

Mucosal thickening (hyperplasia) can typically occur as a consequence of chronic tissue irritation, tumour growth or hormonal disorders. In other cases, atrophy (reduction) of the mucosa is found, most commonly associated with deficiency conditions (Fe and vitamin B or oestrogen deficiency) or some autoimmune conditions. The physiological atrophy of the mucosa often occurs at older age.

Moisture may be subject to change due to various pathophysiological conditions; the healthy mucosa is always wet. Reduced moisture or complete dryness can occur most frequently at Sjögren and Mikulicz syndromes, at dehydration or after the use of certain drugs, such as atropine.

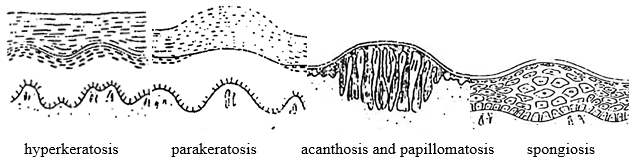

The microscopic picture of mucosal diseases in the oral cavity is only rarely sufficient for diagnosis on itself. In most cases, it can only help classify a particular pathological condition in a certain group of afflictions. Additional diagnostic methods are then usually needed for establishing the exact diagnosis. The schematic view of basic histopathological changes is depicted in Fig. 4:

The schematic view of basic histopathological changes (Záruba et al., 1992)

Hyperkeratosis is a simple thickening of the keratinized layer (stratum corneum); the remaining layers can be thinner, normal or thickened as well. Hyperkeratosis can result from various processes. It clinically manifests as a white patch.

Parakeratosis means imperfect keratinization, which is characterized by the presence of persistent nuclei in the stratum corneum, whereby the layer is thickened, just like in the case of hyperkeratosis. Again, it clinically manifests as a white patch.

Dyskeratosis is another keratinization defect manifesting as premature keratinization of individual epidermal cells, with characteristic corneal granules and bodies formed in their plasma. It is a premalignant change of the epithelium with changes of nuclei, in cell polarity, and presence of mitotic figures.

Acanthosis is a thickening of the epidermis due to pathological multiplication of the cells of stratum spinosum. It is usually accompanied with the extension and enlargement of interpapillary spikes. It may occur together with or without hyperkeratosis. Acanthosis is a common pathological reaction to various stimuli.

Spongiosis is a term used to describe the intercellular oedema with increased intercellular space in the epithelium and prominent intercellular bridges in the stratum spinosum (e.g. in pemphigus).

Hydropic (vacuolar) degeneration develops as a consequence of intracellular oedema and cell degeneration in the stratum germinativum where the cell nuclei are replaced with empty space. The whole cells gradually degenerate and the border between the epithelium and connective tissue is difficult to distinguish (e.g. in lichen planus).

Acantholysis is a process characterized by the dissolution of desmosomes that results in „loosening“ the cells and in the increase in the intercellular space. This in turn leads to formation of intraepithelial blisters (typical of pemphigus).

Epithelial atrophy is manifested by the loss of various layers of the epithelium (particularly of the stratum spinosum). It can develop as a result of several different processes (inflammations, trophic changes).

All diseases of the oral mucosa manifest themselves morphologically by visible lesions that can be divided into primary and secondary efflorescences.

(Fig. 5)

Macule (spot) is a circumscribed red area at the level of the mucosa of various shapes and sizes. It can be either isolated or occur in groups, possibly with individual spots merging together. Erythema covering a larger area of the mucosa is called enanthema (scarlet fever, drug-induced allergies).

Papule (bud) is a small, circumscribed bulge, varying in size and shape, protruding above the surrounding mucosa. Papular eruptions are usually multiple, their colour on the oral mucosa is usually whitish or white-grey. Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a typical manifestation within the oral cavity.

Tubercle (bulge) is actually a large papule, such as a lipoma.

Vesicle (blister) is a small (up to 5 mm), circumscribed, elevated lesion that is, unlike a papule, filled with fluid. A large blister (5 mm to several cm) is called bulla. The contents of the blister is usually clear, the thickness of the blisterʼs roof depends on the location (subepithelial blisters have a thicker roof than intraepithelial blisters). It occurs in the oral cavity during viral infections such as herpetic infections or in blistering diseases such as pemphigus (intraepithelial blister), pemphigoid (subepithelial blister), EEM, or Duhring’s dermatitis herpetiformis (subepithelial blister).

Pustule is a vesicular lesion that is – unlike the vesicle – filled with pus (causing a yellowish discoloration). It occurs e.g. during varicella.

(Fig. 6):

Crack (crevice) results form a rupture of the mucosa. It is most common in the corners of the mouth, on the lip or on the tongue. A deep, bleeding crevice is called a fissure.

Erosion is a mucosal defect characterized by the loss of superficial layers of the epithelium (not including stratum germinativum). It is probably the most common mucosal efflorescence. It can be painful but it heals without scars (e.g. minor aphthae). Aphtha is a specific efflorescence of the oral mucosa. The primary manifestation is a blister; its roof is however lost soon and an erosion develops, the base of which is covered with fibrin. The erosion is surrounded by a red, erythematous halo. It often occurs after a mechanical injury or may result from the loss of the blisterʼs covering in a bullous disease. Sometimes, it may be covered by a pseudomembrane on the mucosa or by a crust on the skin.

Squama (scale) is a flattened plate of the superficially cornified layer that easily separates from the mucosa during hyperkeratosis; it affects the lip red or the skin.

Crust (scab) is a dry exudate on the skin or on the lip red. It does not occur on the mucosa.

Eschar is a result of skin necrosis caused by chemical or thermal burning, after frostbites or as a result of trophic disorders. Initially, the necrotizing tissue is whitish, then turns grey or black. It is sloughed off by circumscribed inflammation, leaves an ulcer behind that heals with a scar.

Ulcus (ulcer) has a deeper loss of tissue than an erosion – the base of the ulcer consists of connective tissue and fibrin with the infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. It always leaves a scar. The edges of the ulcer can be distinct or jagged, elevated or depressed, hard or soft. It is usually round, although linear ulcerations may also occur as a result of mechanical or chemical injury. Like erosions, ulcers can also result from blistering diseases (pemphigus, pemphigoid, major aphthae). The pain depends on the etiology (painless ulcers are associated with carcinoma, syphilis!).

Tumour is a local swelling of the tissue including the mucosa of various sizes. It is a typical symptom of carcinoma, neoplasms or tumour-like lesions, such as pyogenic granuloma.

Besides the type of manifestations present in an individual, the location of the lesion also plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis. For example, eruption of vesicles in the rear part of the oral cavity and oropharynx suggests a possible herpangina whereas the affliction of the gingiva and mucosa in the frontal part of the oral cavity can be a typical symptom of herpetic stomatitis. The presence of vesicles and bullae on the labial mucosa suggests erythema multiforme, which usually also manifests elsewhere in the oral mucosa. The shape and arrangement of efflorescences can also have a diagnostic value (linear, herpetiform, follicular, multiform). The time of the onset (or recurrence) of clinical symptoms can help in diagnosis (e.g. recurrent aphthous stomatitis).

During examination of the oral mucosa, it is crucial to prevent any transmission of contagious diseases (Hepatitis B, HIV, etc). For example, clinical manifestations of HIV may only appear a long time after the contact with the virus and not even laboratory tests are for a certain period (3-6 months) fully reliable. For these reasons, we always abide by the rules ensuring the protection of the healthcare personnel from disease transmission during the performance of their duties as well as protection of patients from the hospital-acquired infections. The basic hygienic regulations must be adhered to during any examination, protective gloves and surgical masks/face shields must be used.

HIV transmission is similar to that of Hepatitis B virus (HBV), the latter is however much easier to transmit. In addition, HIV is very susceptible to heat and most common disinfectants. Adhering to the rules for prevention of HBV transmission therefore provides a sufficient protection from HIV infection as well, no additional measures are necessary. Patients with HIV infection can be hospitalized and examined at any healthcare provider or be clients of social services (see the Guidelines on the Issues of HIV/AIDS infection in the Czech Republic – Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, 2016).

The examination begins at the lips where the symptoms of various diseases can manifest either on the cutaneous (common skin diseases) or on the vestibular part of the lips (mucosal diseases). The vermilion zone is a transitional tissue that is particularly prone to changes, e.g. during fever (dry lips, formation of crevices). The normal labial mucosa is pink, a pale colour is usually associated with poor circulation or anaemia whereas the blue-red colour (cyanosis) is typical of a number of congenital cardiac abnormalities, intoxications and cardiac insufficiency. Blisters and crusts (during infections – particularly herpetic infections) or hyperkeratosis (lichen ruber planus) are the most common symptoms found on the lips. The examination of mouth corners is important as it often reveals painful mouth corners with cracks, macerated skin and crusts.

The gingiva is examined next. The healthy gingiva has a light pink colour, turning red if inflamed or pale in the case of anaemia. Epithelial desquamation – scaling of the superficial epithelium – can also be present, with patches of exposed connective tissue that bleed easily (a typical sign of desquamative gingivitis, pemphigus, pemphigoid, OLP). Bleeding of the gingiva is one of the most common problems in patients with acute or chronic inflammations of the gingiva (most cases, approx. 90 %, are plaque-induced gingivitis); severe bleeding can however occur at gingival inflammation concomitant with serious general diseases. Pain is another serious symptom associated with acute inflammations (ulcerative gingivitis). In chronic inflammations, pain is usually induced (during teeth cleaning, eating, etc.). The condition of the periodontium must be examined thoroughly in order to distinguish true and false pockets (gingival hyperplasia may conceal serious general diseases such as haemoblastosis or tumours).

Subsequently, the tongue shall be examined, focusing on the tongue size, the condition of the tongue edges and tip. The surface of the mucosa of the tongue dorsum depends on the presence of papillae, coating, colour and moisture. Erosions, inflammations of the orifices of salivary glands or leukoplakia (hyperkeratosis) are often found on the floor of the oral cavity.

The vestibular and buccal mucosa often show inflammatory symptoms or hyperkeratosis (oral lichen planus and leukoplakia). On the palatine mucosa, herpetic or allergic changes or hyperkeratosis can be observed.

Hematological tests |

|

Immunological tests |

|

Allergy tests |

|

Biopsy |

|

Microbiological examination

|

|

* performed diagnostic-therapeutic excision with sufficient radicality

Such tests are instrumental for diagnosis of some diseases to verify the diagnosis or to differentiate between conditions the etiology of which is not clear from the clinical picture. They are also important for establishing the sensitivity of the pathogen on the treatment agents (antibiotics, antimycotics, etc.).

It is necessary to perform such tests in patients with symptoms of acute infectious stomatitis (caused for example by the herpes virus) that are severe or prolonged, in ulcerative gingivostomatitis or some other diseases to exclude any potential serious general disease. Routine tests such as erythrocyte sedimentation, complete blood count, differential count of white blood cells and/or CRP test are performed. When indicated (angular cheilitis, glossitis), the full red blood cell count is supplemented with the determination of plasma iron and iron-binding capacity values as well as that of ferritin (an iron-containing storage protein).

The basic haemocoagulation tests (thrombocyte count, Quick test, aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time) shall carried out in cases where coagulation disorders are suspected.

The complete immunological examination should be performed in patients with oral mucosal diseases such as chronic forms of oral candidiasis and recurrent infections caused by herpes viruses, or recurrent aphthae. An examination for autoantibodies is necessary if Sjögren syndrome or other autoimmune diseases are suspected. This examination should also always be performed before administering medication affecting the immune system at the general level (immunosuppressants, immunostimulants).

Biopsy often plays a key role in differential diagnosis in patients with chronic or recurrent conditions of unknown origin. Histopathological or immunofluorescence tests of the excised sample help distinguish diseases with similar symptoms (for example chronic hyperplastic candidiasis from leukoplakia). A diagnostic excision is also performed when an abnormal intraoral manifestation of a disease that does not normally affect the oral mucosa (for example primary TB ulcer) is suspected. A biopsy of the mucosa is also necessary to confirm the diagnosis of "hairy” leukoplakia and all blistering diseases.

The physician must be aware of the circumstances and conditions for performing a biopsy. Contraindications include acute viral diseases of the oral mucosa, ulcerative gingivitis, bleeding disorders, suspected hemangioma or malignant melanoma. The extent of the excision and the site of biopsy are of key importance. Efforts during the diagnostic excision should always be made to collect the entire pathological formation. When the affliction is large, a typical part of the suspected tissue should be collected together with the adjacent healthy tissue. The procedure is usually performed at local anaesthesia; the sample collection should be performed very gently, without traumatizing the tissue unnecessarily. This can be for example done by placing an auxiliary stitch into the collected sample to prevent the forceps from bruising the collected tissue. The mucosa is not disinfected prior to the excision. The patient must be properly instructed about the nature of the procedure and possible postoperative complaints or complications.

The excised tissue is usually placed in a 10% formaldehyde solution. The sample of the tissue (including the shortened stitch) is placed on a gauze square to facilitate orientation during the histopathological examination. A properly filled-in dispatch note must be attached to the specimen. Staining is usually performed using haematoxylin and eosin; special staining techniques may be needed in some cases. In order to distinguish blistering diseases and to confirm the diagnosis of lichen, an examination of non-fixed tissue by the direct immunofluorescence method is necessary to prove the presence of autoantibodies bound to the target tissue (usually, an assay for circulating antibodies using the indirect immunofluorescence method complements this test).

Microbiological examination is used for direct or indirect determination of the causative agent of the particular infectious disease. It also serves for establishing the sensitivity to ATBs. In the everyday clinical practice, it is recommended that the physician agrees the medium to be used and the method of sample transfer with the laboratory that would perform the examination prior to taking the sample. A direct determination of the infectious agent (microscopically, by cultivation) is often impossible (for example due to secondary infections/changes in symptoms). For this reason, indirect (serological) methods are frequently used to prove the presence or absence of specific antibodies or microbial antigens.

For successful isolation of the virus, the following conditions have to be met:

the collection of the specimen must be performed as soon as possible after the onset of the disease (within 2-3 days).

the specimen shall be collected from the site with the highest assumed release of the virus.

the specimen must be stored and transported at a suitable temperature (+4º C).

the dispatch note must be filled in correctly and the respective test tube with the specimen must be labelled properly. It must contain the patientʼs name and surname, birth identification number, health insurer, diagnosis, the date of the sample collection, of the onset of the disease, and the name of the physician who performed the sample collection.

The isolation of the virus is performed using living cells, usually in-vitro cultivated cell cultures (other species such as laboratory mice or chicken embryos can also be used but they are quite expensive). The viral antigen is visualized using labelled, (preferably) monoclonal antibodies binding to it. Depending on the method of labelling, antibodies can be detected either by fluorescence or by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Nowadays, molecular biological methods are used for accurate diagnosis, such as in-situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The principle of the PCR method is that the selected piece of DNA is amplified across several orders of magnitude and the obtained product can be analysed for the presence of specific sequences of bases (for example for the presence of typical viral segments).

This method is based on identification of the presence of specific antibodies in the patient’s serum. In order to be able to interpret the results, one must know the principle and the dynamics of the formation of these antibodies. Out of the five existing classes of immunoglobulin antibodies, IgM and IgG antibodies are the most useful for diagnostic purposes. IgM antibodies are produced first, their production only lasts for a limited period of time and stops within a few weeks. The presence of IgG antibodies reaches the maximum level only several weeks after infection (and may remain lifelong for some infections, making it possible to see whether an individual has had a particular infection in his/her life).

Specific antibodies can be monitored using various methods. The complement-fixation reaction (CFR) is, compared to the methods mentioned below, relatively less sensitive. Its main disadvantage is the need for collection of two samples from a patient approx. 2-3 weeks apart in order to follow the dynamics of changes.

The immunofluorescence method is a more advanced and accurate method. It is based on the principle that some stains emit light after being exposed to UV radiation. If the fluorescent substance is bound directly to a specific antibody and thus used for a direct evidence of the antigen, we speak of direct detection; indirect immunofluorescence requires the use of two antibodies – one (of human or animal origin) reacting to the target molecule and the other, carrying the fluorophore, binding to the first antibody. Enzymatic methods such as ELISA utilize antibodies labelled with an enzyme; after binding to an antigen and washing, the enzymatic activity is measured and is directly proportional to the concentration of the antigen. Another method, radioimmunoassay (RIA), utilizes radiolabelled antibodies for the detection of the target antigens.

Cultivation methods are typically used both for recognizing the responsible bacterial pathogen and to determine its sensitivity to antimicrobial therapy.

As the collection of the biological material is nowadays performed simultaneously for both aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms, protection of the material from the contact with air oxygen is a necessary prerequisite for successful cultivation. It is therefore recommended that the sample should be collected (ideally in the morning on an empty stomach) by means of a smear from the afflicted area of the mucosa using a sterile cotton swab. The swab is then placed on the bottom of a test tube containing a semi-solid transport medium (on rare occasions, it is transported in a test tube containing CO2). Cultivation is then performed on bacteriological media selected depending on the particular (assumed) infectious agent (blood agar, End medium, Fortner medium for anaerobes, etc.). It should be pointed out that anaerobic cultivation is usually much longer than that of aerobic bacteria. The identification of some causative agents such as gonorrhoea (Neisseria gonorrhoea), tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and other infections requires the use of special media.

As an example of microscopic examination, it is possible to mention dark-field microscopy for diagnosing the first stage of syphilis where serum reactions are still negative.

This type of examination is important e.g. when syphilis is suspected; specific serum reactions are used to diagnose the second and third stages.

Similar to the bacteriological examination, it is used to verify the clinical diagnosis and determine the sensitivity of (usually) yeasts to the antimycotic therapy. Smears are performed withthe above-mentioned precautions. Cultivation is usually performed on the Sabouraud agar with the addition of antibiotics to suppress bacterial contamination.

| dermatology examinations | oral lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, lupus erythematodes, contact allergy |

| ophthalmology | Sjögren syndrome, Behçet disease |

| allergological | drug-induced exanthema, Quincke’s oedema |

| immunological | recurrent infections, autoimmune disorders |

| rheumatological | Sjögren syndrome |

| hematology | anemia, haemoblastosis |

| internal/endocrine | diabetes mellitus, hypofunction of thyroid gland, Sjögren syndrome |

| otorhinolaryngology ENT | lesions behind palatal arches, Sjögren syndrome |

Consultations with experts in other specializations is necessary when:

The specialist consultation component may also include an examination by a more experienced dentist or specialist.

The most common consultations called for by dentists include a dermatology examination (SLE, pemphigus), ophthalmology (Sjögren syndrome, Behçet disease), neurological (glosodynia, neuralgia), allergological (drug-induced exanthema, Quincke’s oedema), or haematological (anemia, haemoblastosis) examination, a consultation with an expert in ENT or rheumatology (necessary in Sjögren syndrome), or, if need be, a general examination by a specialist in internal medicine.

The request for consultation should contain a full detailed description of so far performed treatment steps and administered medications (due to a possible change in the clinical picture resulting from the use of medication) including a brief patient history and a suspected diagnosis.